Use DuckDB in ensembldb to query Ensembl's genome annotations

To query genome annotations locally, ensembldb has been my go-to approach. While I’ve already said many good things about this R package (1, 2, 3), here’s a summary of my favorite features:

- I can use the same Ensembl version throughout my project (as a SQLite database)

- I can query the genome-wide annotations and their locations easily and offline

- Nice integration to R’s ecosystem that I can easily combine the extracted annotations with my data and other annotations using GenomicRanges and SummarizedExperiment

- Language agnostic to use its database (say, I can query the same db in Python)

Since DuckDB is designed for analytical query workloads (aka OLAP), I decided to convert ensembldb’s SQLite database to DuckDB and try it in some of my common analysis scenarios. DuckDB has a similar look-and-feel to SQLite. Also, it uses a columnar storage and supports query into external Apache Parquet and Apache Arrow tables. I tried out some of these user-friendly features in this exercise.

Convert ensembldb’s database to DuckDB through Parquet

The first step is to convert ensembldb’s SQLite database to DuckDB1. I decided to export the SQLite tables as individual Parquet files, and then reload them back to DuckDB. So we could also test the DuckDB’s ability to query external parquet files directly.

For this exercise, I used the latest Ensembl release (v107). We can download the corresponding SQLite database from AnnotationHub’s web interface (its object ID is AH104864):

curl -Lo EnsDb.Hsapiens.v107.sqlite \

https://annotationhub.bioconductor.org/fetch/111610

We use SQLAlchemy to fetch the schema of all the tables:

from sqlalchemy import MetaData, create_engine

engine = create_engine('sqlite:///EnsDb.Hsapiens.v107.sqlite')

metadata = MetaData()

metadata.reflect(bind=engine)

We can then list all the tables and their column data types:

db_tables = metadata.sorted_tables

for table in db_tables:

print(f'{table.name}: ', end='')

print(', '.join(f'{c.name} ({c.type})' for c in table.columns))

# chromosome: seq_name (TEXT), seq_length (INTEGER), is_circular (INTEGER)

# gene: gene_id (TEXT), gene_name (TEXT), gene_biotype (TEXT),

# gene_seq_start (INTEGER), gene_seq_end (INTEGER),

# seq_name (TEXT), seq_strand (INTEGER),...

# ...

With the correct data type mapping, we can export all the tables as Parquet by pandas and PyArrow. Since there are quite many text columns, I also used zstandard to compress the Parquet (with a higher compression level):

import pyarrow as pa

import pandas as pd

import pyarrow.parquet as pq

sqlite_to_pyarrow_type_mapping = {

'TEXT': pa.string(),

'INTEGER': pa.int64(),

'REAL': pa.float64(),

}

# Read each SQLite table as a Arrow table

arrow_tables = dict()

with engine.connect() as conn:

for table in metadata.sorted_tables:

# Construct the corresponding pyarrow schema

schema = pa.schema([

(c.name, sqlite_to_pyarrow_type_mapping[str(c.type)])

for c in table.columns

])

arrow_tables[table.name] = pa.Table.from_pandas(

pd.read_sql_table(table.name, conn, coerce_float=False),

schema=schema,

preserve_index=False,

)

# Write each Arrow table to a zstd compressed Parquet

for table_name, table in arrow_tables.items():

pq.write_table(

table,

f'ensdb_v107/{table_name}.parquet',

compression = 'zstd',

compression_level = 9,

)

Load Parquet tables to DuckDB

Finally, we can load the exported Parquet tables to DuckDB. Here I tested a few approaches:

- Create views to the external Parquet files (no content loaded to the db)

- Load the full content

- Load the full content and index the tables (same as the original SQLite db)

Since DuckDB has native support for Parquet files, the syntax is straightforward:

-- Install and activate the extension

INSTALL parquet; LOAD parquet;

-- To create views to external Parquet

CREATE VIEW <table> AS SELECT * FROM './ensdb_v107/<table>.parquet';

...

-- To load the full content from external Parquet

CREATE TABLE <table> AS SELECT * FROM './ensdb_v107/<table>.parquet';

...

-- To index the table (use .schema to get the original index definitions)

CREATE UNIQUE INDEX gene_gene_id_idx on gene (gene_id);

CREATE INDEX gene_gene_name_idx on gene (gene_name);

CREATE INDEX gene_seq_name_idx on gene (seq_name);

...

Note that I didn’t try to “optimize” the table indices for my queries. I simply mirrored the same index definition from the original SQLite database.

DuckDB’s commandline interface works like SQLite. And it keeps the database in a single file too. The full conversion including the Parquet step took about 10 seconds to complete.

duckdb -echo ensdb_v107.duckdb < create_duckdb.sql

duckdb -readonly ensdb_v107.duckdb

Database file size comparison

Here shows the file size of the databases created with different settings:

| Database | File size | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| SQLite no indexed | 243MB | 57.9 |

| SQLite (original) | 420MB | 100.0 |

| DuckDB with external Parquets | 37.6MB | 9.0 |

| DuckDB | 169MB | 40.2 |

| DuckDB indexed | 528MB | 125.7 |

DuckDB with external Parquets yields the smallest file (~9% of the original size). It’s probably due to a lot of text columns in the database, and zstd compression works really well for the plain text. This approach could make the ensembldb database more portable. Say, it’s possible to commit it directly into the analysis project’s GitHub repo.

By loading the actual data into DuckDB (without indices), the file grows considerably due to no compression. Though it is slightly smaller than its SQLite counterpart. I wonder if this is due to the columnar storage being more space efficient than row storage. After indexing the DuckDB database, it surprisingly grows to be much larger than SQLite. I don’t know DuckDB’s indexing methods enough to understand what happened here. Since DuckDB is still actively developing its indexing algorithm, I suppose this could be optimized in the future.

Now we have the databases ready. Let’s see how they perform.

Use DuckDB in ensembldb

It’s painless to tell ensembldb to use DuckDB instead. DuckDB’s R client already implements R’s DBI interface, and ensembldb accepts a DBI connection to create a EnsDb object. So we already have everything we need:

library(duckdb)

library(ensembldb)

edb_sqlite = EnsDb('EnsDb.Hsapiens.v107.sqlite')

conn = dbConnect(duckdb(), dbdir = "ensdb_v107.duckdb", read_only = TRUE)

edb_duckdb = EnsDb(conn)

dbDisconnect(conn, shutdown = TRUE) # disconnect after usage

All the downstream usage of ensembldb is the same from here.

Benchmark the databases

Now we have the original SQLite database and three DuckDB databases constructed with various settings ready to use in ensembldb. Here I tested two scenarios: a genome-wide annotation query and a gene-specific lookup.

To make the query more realistic and complicated, I also applied a filter to all queries to select annotations only from the canonical chromosomes and remove all LRG genes:

standard_filter = AnnotationFilter(

~ seq_name %in% c(1:22, 'X', 'Y', 'MT') &

gene_biotype != 'LRG_gene'

)

I use microbenchmark to benchmark the same query from different databases. It works like this:

mbm = microbenchmark(

"sqlite_noidx" = { <some query> },

"sqlite" = { ... },

"duckdb_parquet" = { ... },

"duckdb" = { ... },

"duckdb_idx" = { ... },

times = 20 # 50 times for faster queries

)

summary(mbm)

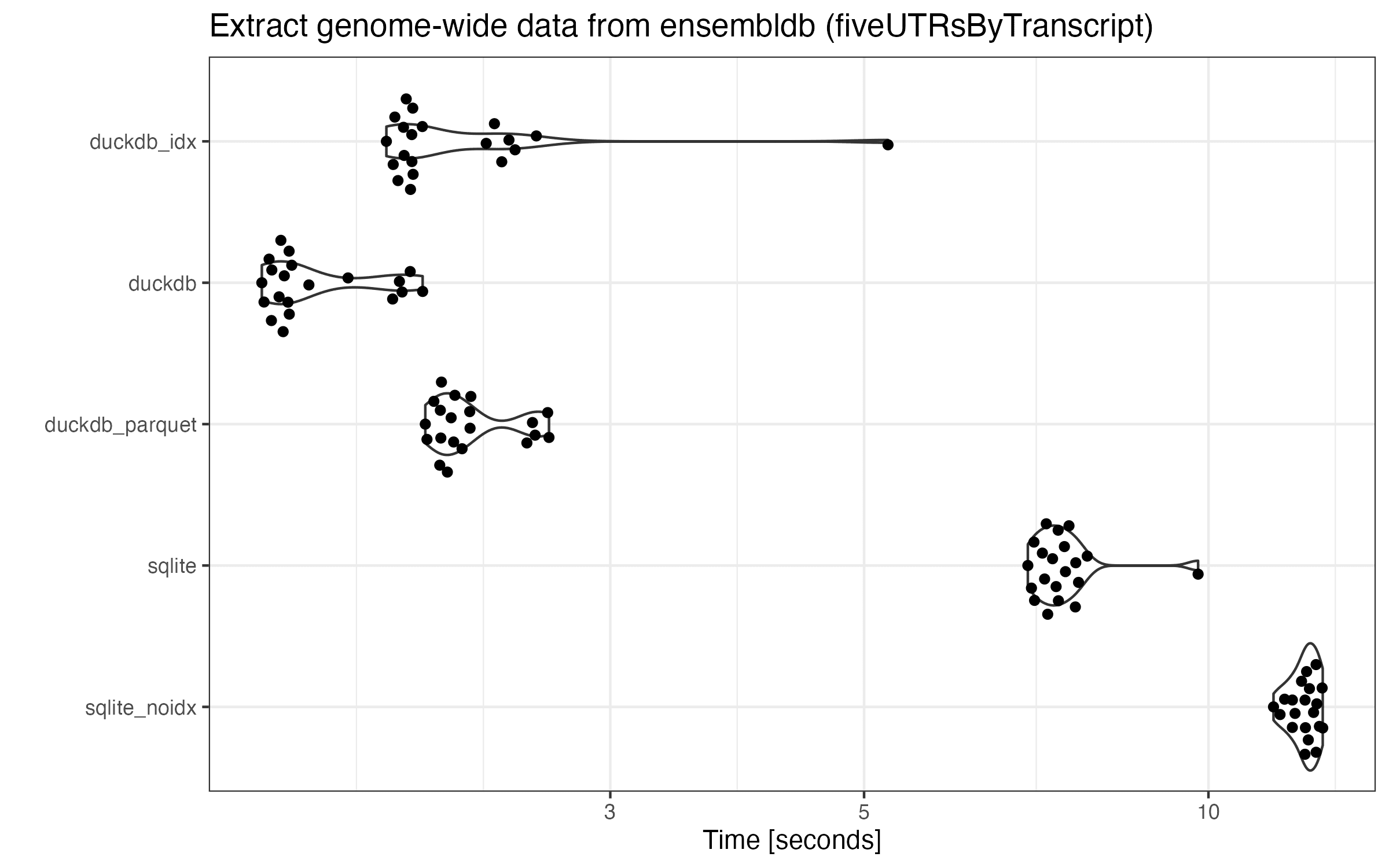

Genome-wide annotation query

The first genome-wide query finds the 5’UTR genomic ranges of all the transcripts. This is one of the most computationally intensive built-in queries I know, involving some genomic range arithmics and querying over multiple tables.

five_utr_per_tx = fiveUTRsByTranscript(edb, filter = standard_filter)

five_utr_per_tx |> head()

## GRangesList object of length 6:

## $ENST00000000442

## GRanges object with 2 ranges and 4 metadata columns:

## seqnames ranges strand | gene_biotype seq_name

## <Rle> <IRanges> <Rle> | <character> <character>

## [1] 11 64305524-64305736 + | protein_coding 11

## [2] 11 64307168-64307179 + | protein_coding 11

## exon_id exon_rank

## <character> <integer>

## [1] ENSE00001884684 1

## [2] ENSE00001195360 2

## -------

## seqinfo: 25 sequences (1 circular) from GRCh38 genome

##

## ...

Here is the microbenchmark results by running the same query in all databases:

There is a huge performance increase for all DuckDB databases, since this query pretty much scans over the full table. Overall, DuckDB runs 3+ times faster than SQLite.

In many cases, there are always a few runs in each database that take significantly more time. This trend is quite consistent as I re-run the benchmarks multiple times. While I haven’t investigated these outliers, I think this is due to the first run(s) being un-cached. Surprisingly, DuckDB with indices run much slower than that without indices (especially the first run). Though the index might be useless in sequential scans, I guess the slowdown could be due to the bigger file (longer to cache) or the query planner accidentally traversing over indices.

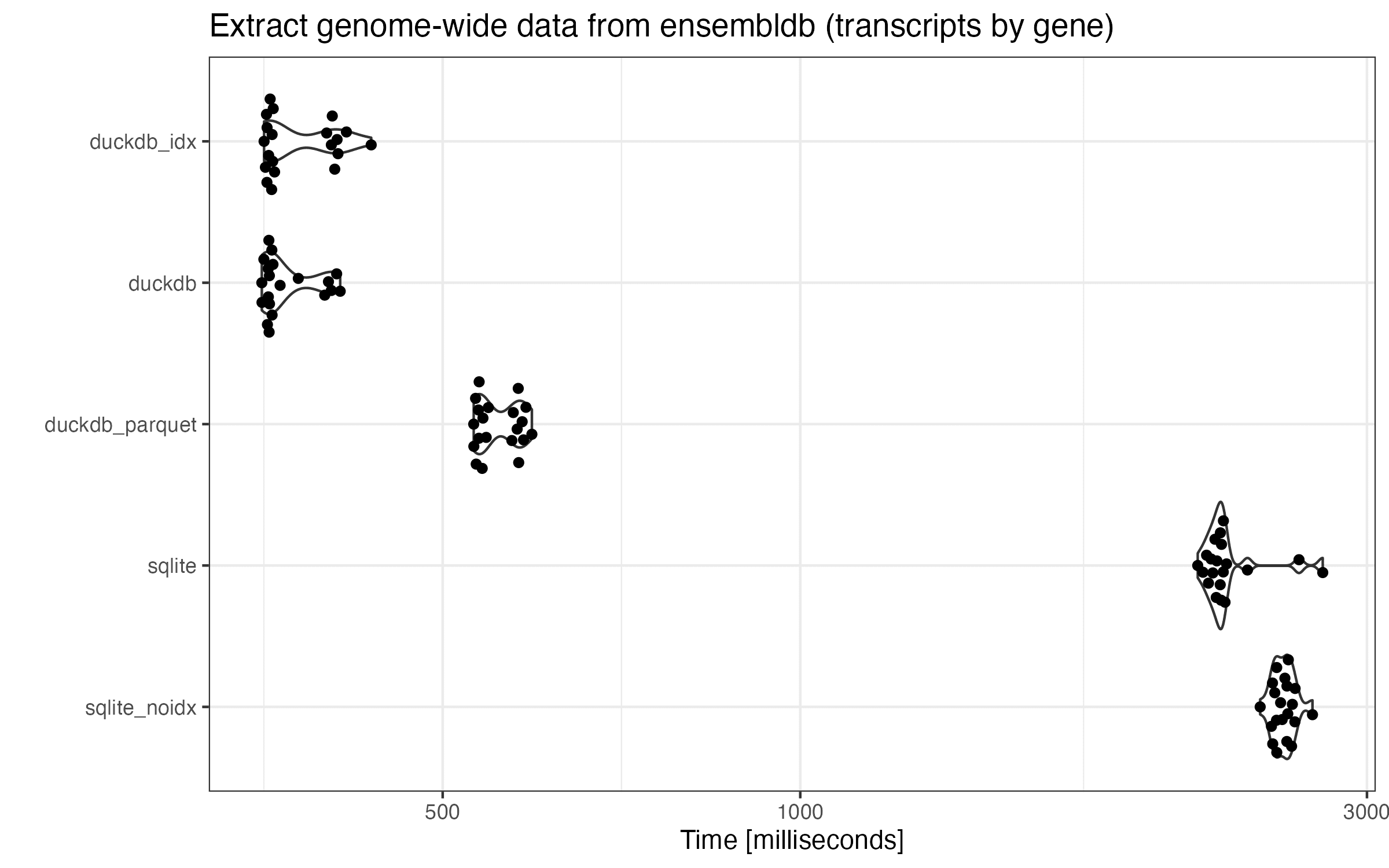

Another genome-wide annotation query

The other genome-wide query finds the transcripts of all the genes.

tx_per_gene = transcriptsBy(edb, by = "gene", filter = standard_filter)

tx_per_gene |> head()

## GRangesList object of length 6:

## $ENSG00000000003

## GRanges object with 5 ranges and 12 metadata columns:

## seqnames ranges strand | tx_id

## <Rle> <IRanges> <Rle> | <character>

## [1] X 100633442-100639991 - | ENST00000494424

## [2] X 100627109-100637104 - | ENST00000612152

## [3] X 100632063-100637104 - | ENST00000614008

## [4] X 100627108-100636806 - | ENST00000373020

## [5] X 100632541-100636689 - | ENST00000496771

## tx_biotype tx_cds_seq_start tx_cds_seq_end gene_id

## <character> <integer> <integer> <character>

## [1] processed_transcript <NA> <NA> ENSG00000000003

## [2] protein_coding 100630798 100635569 ENSG00000000003

## [3] protein_coding 100632063 100635569 ENSG00000000003

## [4] protein_coding 100630798 100636694 ENSG00000000003

## [5] processed_transcript <NA> <NA> ENSG00000000003

## ...

Similarly, here are the benchmark results:

This query tells more or less the same story with only a notable difference. In this case, fully loaded DuckDB with and without indices share the same performance. Interestingly, all the DuckDB runtimes are in a bimodal distribution. I don’t know why.

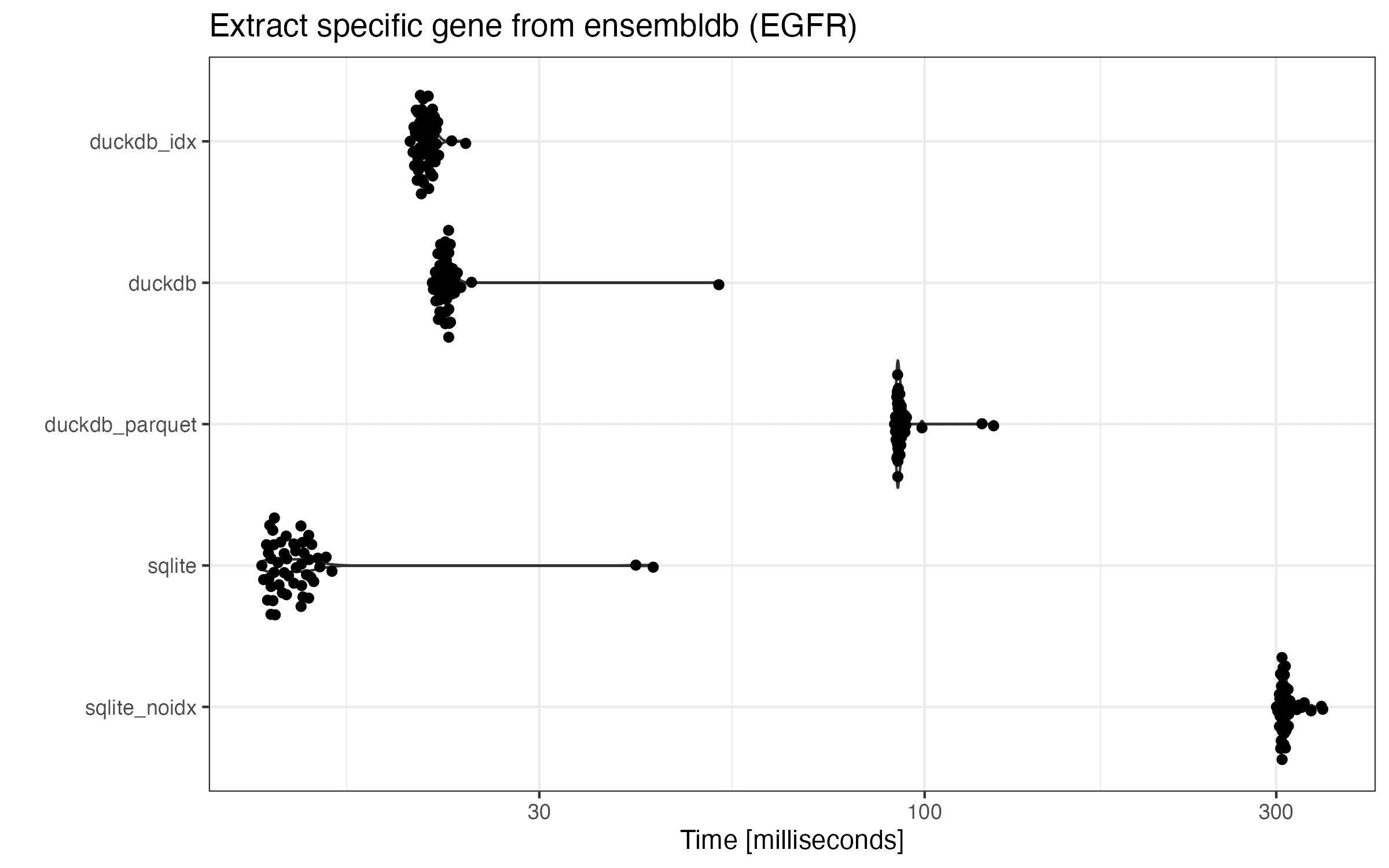

Gene-specific lookup

My another main scenario is to look up the annotations of a specific gene. Let’s simulate this kind of queries by retrieving all the transcripts of a gene “EGFR”:

egfr_tx = transcripts(edb, filter = AnnotationFilter(~ gene_name == 'EGFR'))

egfr_tx

## GRanges object with 14 ranges and 12 metadata columns:

## seqnames ranges strand | tx_id

## <Rle> <IRanges> <Rle> | <character>

## ENST00000344576 7 55019017-55171037 + | ENST00000344576

## ENST00000275493 7 55019017-55211628 + | ENST00000275493

## ENST00000455089 7 55019021-55203076 + | ENST00000455089

## ENST00000342916 7 55019032-55168635 + | ENST00000342916

## LRG_304t1 7 55019032-55207338 + | LRG_304t1

## ... ... ... ... . ...

## ENST00000450046 7 55109723-55211536 + | ENST00000450046

## ENST00000700145 7 55163753-55205865 + | ENST00000700145

## ENST00000485503 7 55192811-55200802 + | ENST00000485503

## ENST00000700146 7 55198272-55208067 + | ENST00000700146

## ENST00000700147 7 55200573-55206016 + | ENST00000700147

## ...

SQLite with indices undoubtedly has the best performance. Understandably, it’s been fine tuned for this very use case (extracting a few rows using indices). And SQLite without an index takes the most time to complete, so it’s necessary to always index the tables.

The performance of all three DuckDB databases fall in between the two extremes of SQLite dbs. Unlike SQLite, indexed DuckDB only speeds up the query a little bit (21.0ms vs 22.4ms on average). Given the worse performance of one of the genome-wide queries above using the indexed DuckDB db, I think it’s optional to create indices for ensembldb’s DuckDB dbs.

Summary

Here is the overview of the benchmarking results together with the db’s file size. The table below displays the performance in average speed-up ratio (and the worst case ratio) over the original SQLite db (ratio the higher the better):

| Database | Size (%) | Genome I | Genome II | Gene-specific lookup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SQLite no indexed | 57.9 | 0.61 (0.78) | 0.88 (1.02) | 0.044 (0.12) |

| SQLite (original) | 100.0 | 1.00 (1.00) | 1.00 (1.00) | 1.00 (1.00) |

| DuckDB w. ext. Parquets | 9.0 | 3.36 (3.69) | 4.14 (4.63) | 0.15 (0.35) |

| DuckDB | 40.2 | 4.70 (4.76) | 6.30 (6.73) | 0.61 (0.81) |

| DuckDB indexed | 125.7 | 3.66 (1.87) | 6.29 (6.33) | 0.65 (1.80) |

Overall, DuckDB shows impressive performance increase for genome-wide queries. It uses up less storage too. While DuckDB is slower than SQLite when it comes to gene-specific lookups, since we are talking about tens of milliseconds per query, unless we are running thousands of these queries, the performance impact is minimal. On the other hand, genome-wide queries are saving seconds per query.

As the benchmark results shown, we could replace the original ensembldb database with a DuckDB database by loading the tables and removing the indices. If the user is willing to sacrifice some performance in gene-specific lookups, DuckDB with external Parquet files only uses < 10% of the original disk space but it still runs faster for genome-wide queries.

While the default indices copied from SQLite are not very helpful, I didn’t tune the indices to maximally speed up the gene-specific lookups. We can probably also tune the Parquet compression ratio to find a better balance between the decompression speed and file size. Note that DuckDB’s file format is not stabilized yet, so the database needs to be re-created in newer DuckDB versions.

All in all, I think DuckDB advertises itself accurately when it comes to analytical query workloads. It shows good performance when it queries a large portion of its content. By having a similar interface to SQLite and clients in popular languages (R, Python, and etc), it’s easy to change an existing SQLite usecase to use DuckDB. My small exercise with ensembldb has convinced me to try out DuckDB in more scenarios too.

-

There is an official extension sqlite_scanner currently under development that lets a DuckDB attach directly to a SQLite database. So in the future, it could be much easier to convert SQLite to DuckDB. ↩